The Collector’s Gaze: Henry Dresser at Manchester Museum

In an era defined by biodiversity loss, there’s growing urgency in how we look at the natural world, and how we remember the ways it was once studied. The recent acquisition of the author’s copy of A History of the Birds of Europe and the accompanying display in the Living Worlds gallery at Manchester Museum brings this tension into sharp focus.

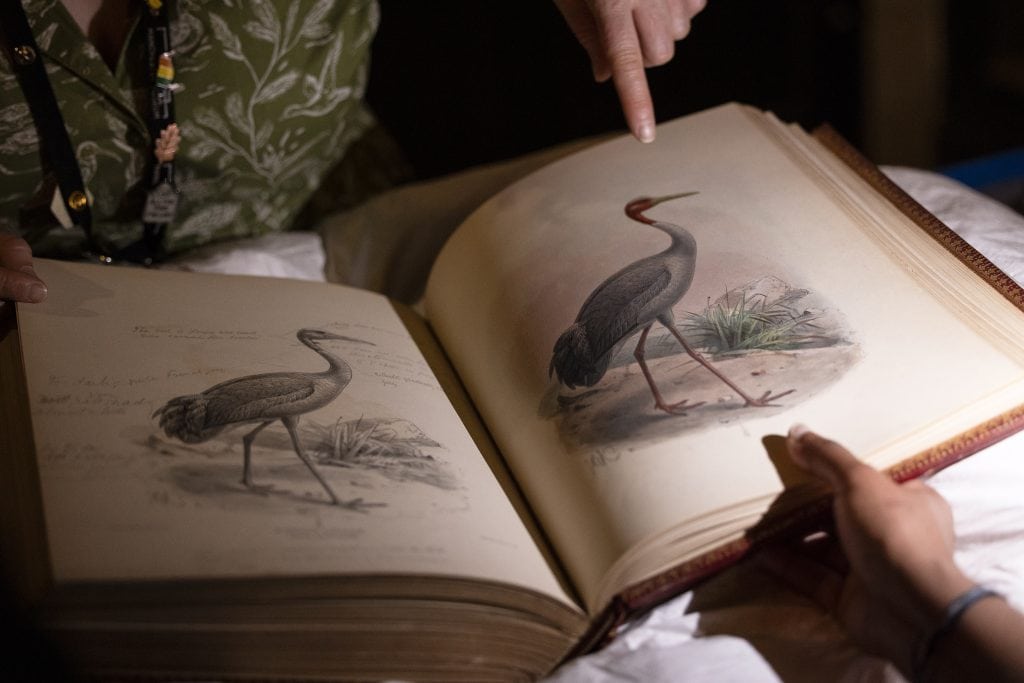

The illustrations are vivid, with each bird rendered with the precision of scientific observation reflecting author Henry Eeles Dresser’s own ornithological passion. This set of books is widely considered a landmark of Victorian ornithology. It’s an elegant fusion of science and art, bound together with the meticulousness and obsession of collecting. But the story this publication tells is not just one of ornithological passion. It’s also a story of empire, extraction, and the uneasy legacy of collecting.

As museums across the UK and beyond grapple with their colonial inheritances, the acquisition and display of these books highlight important questions around the role of museums in making these tensions visible, rather than burying them beneath glass and gloss.

The Collector and His World

Henry Dresser (1838–1915) was, in his time, one of the most important ornithologists in Europe. Born into a wealthy merchant family with ties to the Baltic timber trade, Dresser spent his formative years in Sweden, Germany, and New Brunswick in Canada, before working in Mexico and Texas during the American Civil War. There, he served as a commercial runner, a go-between moving goods across contested borders and blockades. This role placed him at the fringes of a fractured nation and exposed him to the logistics and risks of operating in imperial spaces.

He eventually settled in London, where he balanced a career in iron and timber with his consuming passion for ornithology.

He began collecting eggs as a teenager and never stopped. Over the course of his life, Dresser amassed around 60,000 bird eggs and more than 10,000 specimen skins. This was a world before digital databases or wildlife photography, so these collections were integral in the foundation of western scientific ornithological knowledge. Ultimately, his goal was encyclopaedic, to document every bird species in the world and map its range with as much precision as possible.

Dresser published more than 100 scientific papers and several monumental books, including A History of the Birds of Europe. He was deeply embedded in the global network of naturalists and collectors that connected scientists, missionaries, trappers, geographers, and hobbyists across the British Empire and beyond. ‘Europe’, as Dresser understood it, extended far beyond today’s political boundaries, as far as Russia, Central Asia, and North Africa. Now we are able to view his practice within the context of the politics and power structures of the time, revealing it to be part of a wider attempt to catalogue, classify, and ultimately control the natural world and the people within it. This was a world where collecting was not neutral, but an extension of power. The definition of where species belonged could also be extended to who had the authority to speak about them.